For many women, comes as a relief: an end to pregnancy worries and monthly cramps, a farewell to bloodstained panties and premenstrual mood swings. Though menopause signals the opening of a historically uncelebrated chapter in a woman’s journey, lots of women are thrilled to cross its threshold.

Others loathe the passage. For them it’s a journey often punctuated by hot flashes, insomnia and, in numerous cases, sexual dysfunction — symptoms that for some can continue for 15 years or longer. These episodes can make women in their 50s and 60s feel uncomfortable, demoralized and sometimes seriously ill.

But regardless of one’s attitude toward it, the onset of menopause means a marked increase in certain health risks. For example, hormonal changes result in an accelerated rise in LDL cholesterol in the 12 months following menopause, boosting the possibility of heart disease. And though both men and women suffer a loss of bone density with age, the sudden reduction in estrogen associated with menopause has been shown to trigger an inflammatory reaction in some women that leads to a dramatic decrease in bone mass. These issues lurk beneath a host of distracting and sometimes debilitating physical conditions, large and small, from night sweats to weight gain to concentration problems.

And though menopause medications that can help alleviate discomfort — and perhaps prevent or delay the onset of chronic disease — have been around for decades in various forms, research indicates that just a small minority of menopausal women are receiving the medical care they deserve. A Yale University review of insurance claims from more than 500,000 women in various stages of menopause states that while 60 percent of women with significant menopausal symptoms seek medical attention, nearly three-quarters of them are left untreated.

“Doctors are not helpful,” says Philip M. Sarrel, professor emeritus of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive services, and of psychiatry, at the Yale School of Medicine. “They haven’t had training, and they’re not up to date.”

“Nearly one-third of this country’s women are postmenopausal,” says gynecologist Wen Shen, an assistant professor in the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics. “Many of them are needlessly suffering.”

“Doctor, what’s happening?”

Carrie Haine is in tears. She is petite, attractive, the type of woman whom you easily envision as a popular “it” girl when she was in high school or college. Now the former third-grade teacher is 57, and while she has had some relief lately, her body has been betraying her. Sleep has grown elusive. Hot flashes have stolen her focus. Sex has hurt.

“It’s a hard thing to face,” says the mother of two grown sons. “Your intimate understanding of your body changes.”

Haine had been trying to figure out her problem since she went off the pill four years ago. Because birth control pills contain estrogen, they can mask the onset of menopause. Within three weeks of discontinuing them, hot flashes hit Haine “like huge waves rolling into shore, then crashing on the beach,” punctuating her days “with an intensity that only someone who has experienced them can understand.” In time, she grew inexplicably anxious and soon started losing track of thoughts, often finding herself without words. She knew she was going through “the change,” yet hadn’t been prepared for “how all encompassing it was — that it wasn’t just about my body but everything about me, and I felt it not only physically but emotionally.”

Haine consulted with the male gynecologist who delivered the second of her two sons. “I didn’t feel he understood the emotional aspects of what I was going through,” she says. “And I felt he wasn’t attuned to the nuances of my body.” Later she consulted with a “lovely” female gynecologist who attempted to solve her sex-pain issue with gels and sex toys.

Then, last year, Haine had a horrifying experience. One day while at work, she got so dizzy she had to sit down. But what really concerned the school nurse was Haine’s sudden inability to speak. “I had the words, but I couldn’t say them,” she remembers. Worried that Haine was having a stroke, the nurse called an ambulance. But at the hospital, all her scans and blood work checked out. Said the doctor when he signed her discharge papers, “Maybe you need a hobby.” Turns out, Haine needed neither a sex toy nor a hobby; she needed a physician who understood how to treat menopause.

Haine tells her story from Shen’s meeting room in the Lutherville, Maryland, offices of Johns Hopkins. A few months before, Haine heard Shen speaking on the radio, on NPR. “She was talking about menopause, and her voice was really calm and soothing, and it resonated with me,” says Haine, who, like many women, and even many doctors, didn’t generally associate a shift in hormone levels with anxiety. She also didn’t realize she could find a solution for painful sex, which has since been eased with vaginal estrogen. During this latest visit, Shen is referring Haine to a psychologist to help her with some of the emotional changes that can accompany menopause for some women. “She’s looking at all the bits of me,” Haine notes. “Not just my body and how it’s changing but also how I am changing as a woman. Menopause is very personal.”

“I can’t tell you the number of women who walk out of my consultation and say, ‘Thank you so much. You’ve validated me for the first time in years,’ ” says Shen, the renowned medical school’s sole dedicated practitioner for menopause consultations. “I’m always happy to hear that, but it also makes me really sad.”

That’s because properly treating menopause symptoms can do more than afford women extra sleep, less anxiety and a better sex life. When their menopause is properly managed, particularly from the beginning, women may lower their risk for many of the common, life-threatening diseases that can mark their next quarter-century and beyond. For example, a 2017 study found that the more severe and longer lasting a woman’s hot flashes and night sweats are, the greater her risk for developing type 2 diabetes. Other studies have shown that treatment at the onset of menopause can slow the progression of osteoporosis.

“When we talk about menopause, we’re not just talking about hot flashes and night sweats and dry vaginas,” Shen points out. “We’re talking about what happens after the ovarian hormones go away and women become at increased risk for osteoporosis, heart disease, cognitive decline.” In other words, menopause accelerates aging. A 2013 study stated that “menopause is an independent risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease.” And menopause “means the loss of a key neuroprotective element in the female brain and a higher vulnerability to brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease,” asserts Lisa Mosconi, a professor of neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City and lead author of a study on menopause and dementia in the journal PLOS One. It wasn’t until 1908 that a woman’s life expectancy topped 51, the average age of menopause onset. Today, American women can spend a third or more of their lives in this state, many of them without recourse for symptoms and conditions they were never warned about and thus not prepared for.

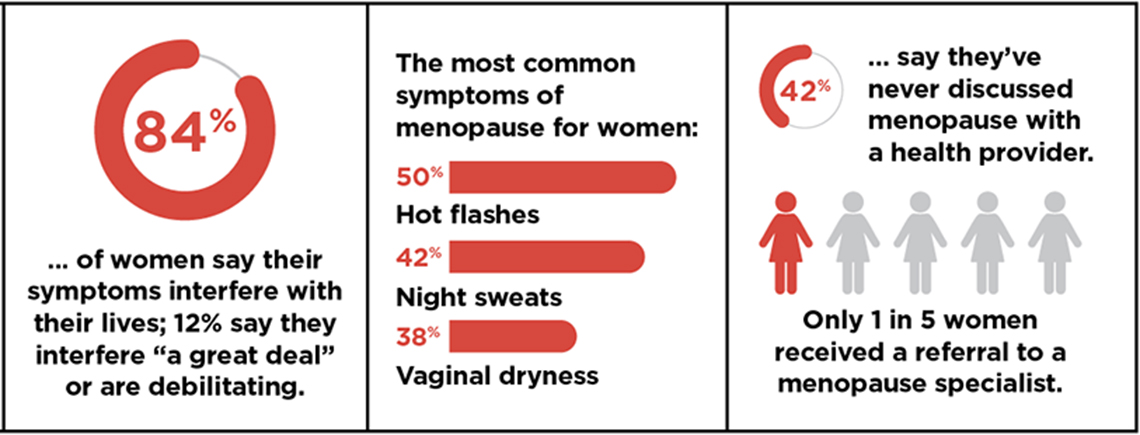

AARP surveyed more than 400 women between ages 50 and 59 to ask about their experiences with, and attitudes toward, menopause.

The untreated generation

Most medical schools and residency programs don’t teach aspiring physicians about menopause. Indeed, a recent survey reveals that just 20 percent of ob-gyn residency programs provide any kind of menopause training. Mostly, the courses are elective. And nearly 80 percent of medical residents admit that they feel “barely comfortable” discussing or treating menopause.

“Do most practicing ob-gyns have sufficient nuanced knowledge about menopause and how to treat its symptoms?” asks gynecologist JoAnn Pinkerton, executive director of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS). “I don’t think so.” Pinkerton surveyed more than 1,000 medical professionals (including doctors, physician assistants and nurse practitioners) regarding their knowledge of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for menopause symptoms. Only 57 percent of physicians were up to date on their information, according to the survey’s results.

Every woman’s menopause experience is different, and many cruise through the natural decline in estrogen without significant discomfort. But for too many women who are experiencing serious symptoms, the response of the average doctor is simply, “There’s nothing we can do.”

“We spend a lot of time in the health care profession teaching women how not to get pregnant,” says New York City gynecologist Tara Allmen, author of Menopause Confidential. “Then we teach them how to have babies, and possibly we teach them how to breastfeed. But that is where the lectures end.”

Approximately 6,000 women in the U.S. reach menopause each day. By 2020, 50 million women will be postmenopausal. According to NAMS, about 75 percent of women experience some kind of menopausal distress. And for some 20 percent of these women, symptoms — in particular hot flashes and night sweats — are severe enough to interfere with just about every meaningful aspect of their lives: sleep, work and relationships. Severe symptoms typically last up to seven years; 15 percent of women who have hot flashes suffer with them for more than 15 years.

To better understand the state of menopause treatment, Shen and her Johns Hopkins colleague Mindy Christianson, an endocrinologist and gynecologist, sent surveys to directors at 258 ob-gyn residency programs nationwide. The Hopkins surveys revealed that, across the country, more than half of fourth-year ob-gyn residents who responded (those poised to start seeing patients and building practices) thought they needed more education about menopause medicine, especially regarding hormonal and nonhormonal therapy, bone health, heart disease and metabolic syndrome — issues of utmost importance to postmenopausal women.

Less than half of fourth-year residents felt well versed in osteoporosis, essential to menopause management, as studies find that fractures and breaks from falls can cause premature death in patients over age 45. And nearly two-thirds of the ob-gyn residents reported not feeling knowledgeable enough about the connection between menopause and cardiovascular disease, particularly astonishing given that heart attack is the leading killer of older women. “We expected that residents wouldn’t know much about menopause,” Christianson says. “But these numbers are powerful.”

The bread and butter for Christianson, a reproductive endocrinologist, is helping women get pregnant. But as a hormone specialist, she also sees menopausal women who pack her office to get help for conditions their regular gynecologists don’t want to address. “There’s a huge demand for menopause doctors,” Christianson says, “but a lot of providers are uncomfortable treating it.”

“Menopause is as different from obstetrics as surgery is from pediatrics,” says James Woods, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Rochester School of Medicine in New York. Once an obstetrician, he now specializes in menopause. “Every woman’s ovaries will age and then stop producing estradiol, the body’s most important estrogen. But each person will be different in how she reacts to that loss,” observes Woods, who writes a blog called menoPAUSE. “Menopause management requires a lot of listening. There are no ‘packages’ that can be given to all women.”

Estradiol is one of the body’s most powerful anti-inflammatory hormones. With its decline, the bodies of some women become vulnerable to inflammatory proteins that discombobulate the body’s heat center (ergo, the hot flashes) and deregulate metabolism and digestion (ergo, weight gain and obesity) while increasing LDL cholesterol. Intestinal proteins shift, too, leading to more of that hard-to-lose, but impossible-to-miss, visceral belly fat. The combination of these inevitable events — occurring at different rates in different bodies — is the No. 1 cause of cardiovascular risk for postmenopausal patients.

For more than half a century, one primary answer to these issues has been HRT. A wide variety of therapies are available; when carefully monitored by a physician, prescribed in the lowest effective dose and used for the appropriate amount of time, HRT can reduce both the symptoms of menopause and the long-term dangers associated with it. Though most women would benefit from treatment just during the earliest and most severe onset of menopausal symptoms, when properly supervised, some patients can benefit from HRT for decades, says internist JoAnn Manson, chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

But menopause management is a highly skilled subspecialty, one that requires a full understanding of how plummeting estrogen affects every system in the body. It pays less than other subspecialties because, in many cases, it requires little more than a long annual office visit, one that delves deeply into the patient’s medical history. “The reality is that treating menopause may not be as profitable as delivering babies or doing surgery,” says Allmen, who transitioned to midlife medicine after a decade in the delivery room. “The younger generation of doctors are less interested in the aging population, where the issues require more time but also offer less compensation.”

A menopause renaissance?

When Chicago gynecologist Lauren Streicher stood before the powers that be at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago and proposed the Center for Sexual Medicine and Menopause, “it wasn’t like they jumped up and down and said, ‘What a great idea,’ ” she recalls. They needed convincing. Streicher’s argument: Medical innovation leads to longer lives. But what are a few more years without a good quality of life? “There was a huge unmet need that no one seemed to know about.” So huge that when the center opened in October 2017, its schedule was filled through the next month. “I kept saying to the hospital administration, ‘This is going to be a very busy clinic,’ and they’re, like, ‘Yeah, yeah. Clinics don’t get busy that quickly.’ And I’m, like, ‘Yeah, you just wait and see.’ ”

What makes Northwestern’s clinic stand out, Streicher says, is that it’s not just about treating menopause; it’s about reconsidering the midlife woman’s entire health profile. “Menopause touches every aspect of a woman’s overall health,” she continues. That’s why she has established a collaborative network of subspecialists in every field from cardiology to neurology, all of whom are well versed in the nuances of menopause. Plus, she has a nutritionist on call. “It’s a rare menopausal woman who doesn’t have something else going on medically,” she points out.

Streicher’s next hurdle is making menopause education a requirement in the ob-gyn residency at Northwestern. Beginning next year, it will be an elective; so far, only a couple of the program’s ob-gyn residents have signed up. “I want to change that,” she says, noting that she intends to make menopause management a course that’s available to residents of every subspecialty. “Women will go to their gynecologist, their internist, their family practitioner, and more often than not, they don’t get the help they need,” Streicher adds. Most of her patients found her clinic through word of mouth or because they read an article somewhere. “They walk in the door and say, ‘I told my doctor that I was having hot flashes and vaginal dryness, and he was very dismissive.’ ”

“Menopause management needs to be comprehensively integrated into medical curricula and residency training across primary care as well as a number of subspecialties,” Manson maintains. “The fragmentation of women’s health care has led to untreated symptoms and a serious impact on women’s health. Many women who would have benefited from hormone therapy may have suffered needlessly.”

Shen is a tad more blunt: “I have been bashing my head against the wall trying to make menopause medicine a thing.” She is currently working with a $250,000 grant from Pfizer to develop a menopause app that crosses medical platforms. “There are estrogen receptors on every single organ in the body,” she explains. “We can’t just ignore menopause and say, ‘There, there, sweetie. Just buck up and deal with it.’ ”

To combat this practice and to fill in knowledge gaps, NAMS offers physicians continuing education courses on menopause, as well as certifications in the field of midlife medicine. To date, NAMS has certified more than 1,100 doctors in menopause management, which means they have passed a test indicating a working knowledge of hormonal and nonhormonal therapies to treat menopause symptoms and are up to date on current research. “It can be hard enough to be menopausal,” NAMS’ JoAnn Pinkerton says. “Women deserve to have a provider who understands menopause and can guide them through it.”

The NAMS website is an excellent storehouse of information on menopause.

A panel of top experts answer your questions; plus, there is info on clinical trials.

MenoPro App

A personalized app, it can help you identify what treatments are best for you.

This content was originally published here.